Different Perspectives – One Fate

The Oneg Shabat Archive: A Documentation Project and a Historical Underground

The Oneg Shabat Archive was founded in the autumn of 1940 by historian Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum in the Warsaw Ghetto. The underground name was chosen because members of the group used to meet on Saturdays.

The establishment of the Oneg Shabat Archive was not a spontaneous act, but the result of a deep historical vision and moral vision. Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum, as a historian and researcher of Jewish society, understood the significance of historical documentation right at the beginning of the Nazi occupation, even before the scale of the impending disaster became clear.

The motives for establishing the archive stemmed from several central insights:

- The Need for a Jewish Narrative: Ringelblum understood that the Nazis controlled all means of official communication and documentation, and that in the absence of independent Jewish documentation, the story of the Holocaust could only be written from the perspective of the perpetrators.

- Understanding the Historical Dimension: As an academic, Ringelblum recognized the historiographical value of documenting events in real-time. He saw the archive as a means of preserving the memory of the rich Jewish community of Warsaw.

- Cultural Resistance: The archive represented a form of non-violent resistance to the Nazi attempt to erase Jewish culture. The very act of documentation was an expression of the fact that the Jews refused to disappear from the pages of history.

- Testimony for Historical Justice: Ringelblum believed that one day the Nazis would be brought to trial, and the materials collected in the archive would serve as evidence of the cruel treatment of the Jews.

What makes the Oneg Shabat Archive project particularly remarkable is the objectivity that guided its members. Despite personal suffering and daily hardships, they aspired to document reality in as balanced and accurate a manner as possible. The archive included not only testimonies about Nazi atrocities but also documentation of the complexities of internal life in the ghetto, including criticism of the Judenrat (Jewish Council) and the Jewish police.

“Everything must be documented without omitting a single fact. And when the time comes and it will come the world will read and know what the murderers did” – Emanuel Ringelblum

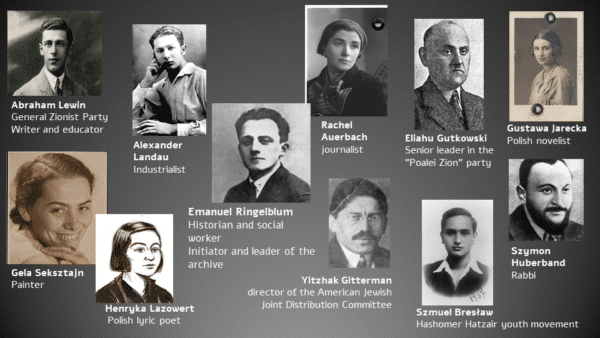

The archive operated in complete secrecy as an underground enterprise and included about 60 members from different backgrounds: historians, writers, teachers, intellectuals, and representatives of political parties.

These are pictures of some of the members of the underground, one can impress from the difference between them in the fields of occupation, the political affiliation, gender and more.

members of Oneg Shabat Archive

Part of the archive survived, and its documents are today one of the most important sources of information for understanding the lives of the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto. In 1999, UNESCO recognized the documents of the Oneg Shabat Archive as part of the “Memory of the World” a collection of documents of universal historical significance.

The Meaning of the Archive – An Act of Hope

The very establishment of the archive and the persistence in its work, even after it became clear that most of the Jews of the ghetto were being sent to extermination, was an act of hope and faith in the future. The members of the archive operated out of a belief that a day would come when the history they were documenting would be revealed, studied, and used as testimony and memory.

Rachel Auerbach, a member of the archive who survived the Holocaust, described how, at the time the documents were buried, Ringelblum said: “I believe that a day will come when people will read our words, understand our suffering, denounce the acts of evil, and honor our strength to endure.”

The significance of the Oneg Shabat Archive as an act of cultural resistance is well expressed in the words of Holocaust historian Israel Gutman:

“The Oneg Shabat Archive was not just a collection of documents; it was an act of spiritual resistance. In creating the archive, the Jews said: ‘You can murder our bodies, but not our spirit; we will write our history, not you.’ This is proof of the victory of the human spirit, even when the body is defeated.”

Challenges of Life in the Ghetto – Coping and Solidarity

The Warsaw Ghetto, established in November 1940, was the largest Jewish ghetto in occupied Europe. At its peak, over 450,000 Jews were crowded into an area of approximately 3.4 square kilometers – more than 30% of the population of Warsaw, in an area that constituted less than 2.5% of the city’s area. The extreme density, along with the Nazis’ deliberate policy of creating impossible living conditions. In many testimonies, these challenges can be found:

Starvation

The official food ration for Jews in the ghetto was about 184 calories per day (compared to 2,500 calories recommended for an adult). The consequence was sustained and severe malnutrition.

Density

On average, 7-8 people lived in one room. Entire families were forced to share small apartments with other families.

Diseases, Epidemics and Mortality

Between October 1940 and July 1942 (before the start of the deportations to Treblinka), 83,000 Jews died in the ghetto from starvation, disease and poor living conditions.

Collapse of the Family and Social Order

In addition to the breakdown of normative frameworks of education, welfare and public order, the family unit also experienced a reversal of roles as children were forced to provide for their families and adults struggled to function in the chaos that had been created.

See the following excerpt from the testimony of Simcha Rotem.

How can civil society in the ghetto cope with the harsh living conditions? How can mutual guarantee be expressed in this reality? What is exemplary behavior and leadership in light of these challenges?

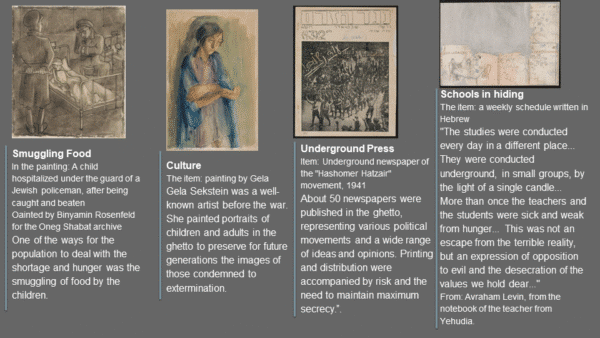

Here are 4 images depicting different ways of coping. Which one expresses the idea of mutual guarantee? Try to choose one that is most relevant to the values of today (there is no one correct answer but only different thought).

Jewish Youth Movements and Their Special Role in the Ghetto

Warsaw, which was a thriving Jewish center before the war, was characterized by a rich cultural and social life, where youth movements were a central part in shaping the identity of young Jews. The movements, in their different shades, reflected the ideological and political diversity of Jewish society in Poland between the two World Wars.

Zionist Movements

HaShomer HaTzair, Gordonia, HeHalutz, Beitar and others, advocated a return to Zion, agricultural training and self-fulfillment. They prepared their members for immigration to Israel and a life of work and pioneering.

Socialist Movements

Tsukunft (The Bund), Yugent (Communist), and others, saw the future of the Jews as part of the class struggle and aspired to social equality in Poland itself.

Religious Movements

Tzeirei Agudat Yisrael, HaShomer HaDati, and Akiva HaMasortit, which combined traditional Jewish-religious education with engagement with the challenges of modernity.

One of the prominent characteristics of the youth movements was their unique educational structure, which was based on principles of informal education, autonomy, self-leadership, and the creation of an alternative “youth society.” Activities included trips, summer camps, cultural evenings, youth newspapers, the study of Hebrew and Jewish culture, and in the Zionist movements also practical training for life in Israel.

Youth Movements in the Ghetto

With the establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto and the imposition of severe restrictions on the Jewish population, the unique strength of the youth movements became apparent. The organizations, which mainly operated in informal education before the war, were now required to fulfill critical and diverse functions in the physical and spiritual survival of the community. Members of the youth movements were among the first to organize to deal with the new challenges and became the backbone of rescue and resistance efforts.

Humanitarian Aid and Welfare

In the reality of starvation and deprivation, the youth movements became centers of relief activities:

- Public Kitchens: Members of movements such as “Dror,” “HaShomer HaTzair,” and “Akiva” were active in establishing and running public kitchens that provided meals to children and adults.

- Childcare: Establishing “Points” meeting places for children and teenagers whose parents were forced to work or had become orphans. In these places, children received a meal, help with their studies, and social and cultural activities.

- Aid to Refugees: Assisting refugees who arrived in the ghetto from other towns and villages, finding housing and food.

One of the prominent features of the activities of the youth movements in the ghetto was the ability to adapt the youth movement ideology to the new conditions. For example, the Zionist movements, which advocated agricultural training and immigration to Israel, now focused on immediate survival and preserving the human values and solidarity.

“Kibbutz Dror resided on Nalewki Street 33. I would see them going to work singing, returning singing. They encouraged the depressed, desperate people loitering the streets. Their lifestyle instilled hope in the ghetto residents.” – Testimony collected at the Oneg Shabat Archive

Another important role played by members of youth movements was in the field of information and documentation:

- Contact with the “Outside World”: Members of youth movements, especially young Jewish women who could pass as Poles due to their “Aryan” appearance, served as “couriers” transferring information, letters, and money between the ghetto and the Polish side of the city.

- Underground Press: Producing leaflets and youth movement newspapers in conditions of secrecy, which brought the residents of the ghetto reliable information from outside sources and served as a platform for ideological discussion.

- Cooperation with the Oneg Shabat Archive: A number of members of various movements were among the activists in collecting materials for the archive, at their own risk.

The Transition to Armed Resistance

With the start of the mass deportations to Treblinka in August 1942, the members of the youth movements came to the realization that the Nazi solution was total annihilation. At this stage, there was a significant shift in their activities from humanitarian aid and cultural rescue to organizing armed resistance. On July 28, 1942, representatives of various movements – “HaShomer HaTzair,” “Dror,” “Akiva,” “Gordonia,” and “Bund” – convened and established the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB).

Members of the youth movements formed the backbone of the armed resistance in the ghetto, and led the uprising that broke out in April 1943. Leaders and leaders such as Mordechai Anielewicz (HaShomer HaTzair), Zivia Lubetkin and Yitzhak Zuckerman (Dror), Meir Breslav (Gordonia) and Marek Edelman (Bund), were all active in the youth movements before the war, and drew their values of determination, responsibility and dedication to the public in these frameworks.

Analyze the moral dilemma it raises